Many of us remember Anonymous’ threat to trigger a global internet blackout back in 2012.

The hackers were allegedly planning to DDoS the root DNS servers of the internet. The goal was to make it impossible to obtain information via domain name-based queries.

In the theoretical aftermath of this disruption, entering google.com or another random URL in a web browser would return an error page, thus making most users think the World Wide Web was down.

Nowadays, the average non-tech-savvy person thinks of the internet as a Wi-Fi connection. Few people know that the bulk of its infrastructure is waterborne and what an immense amount of data is transmitted over this network of underwater channels. Although the capacity of this system is over and above the actual need, it is fairly susceptible to sabotage and may be physically demolished someday.

Before I proceed, let me get something straight: I’m by no means encouraging anybody to engage in any form of destructive activity. Instead, I’m warning of the potential threats we must guard against.

Destroying submarine cables

Those interested can easily access the details on these undersea cables by visiting TeleGeography’s Submarine Cable Map.

There are also plenty of reports covering incidents where different components of this network were damaged. Those that ensued from earthquakes or tsunamis typically devastated the system’s major segments. Nonetheless, even when Japan suffered from a tsunami and many cables were affected, the connection persevered thanks to back-up satellite channels.

Not only is the internet a virtual ecosystem, but also a physical network where cables transmitting the signal play a crucial role but are, essentially, one of the weak links.

It makes sense for would-be saboteurs to single out one of the major vulnerabilities: the concentration of network nodes. According to publicly accessible maps, there are several main points of such a congregation, including underwater ones. Therefore, a natural calamity damaging submarine channels doesn’t appear to be as detrimental as network destruction at the level of communication nodes.

Although corporations keep the exact location of many such cables and their landing stations secret, plenty of them are actually based at popular beaches of noisy cities. Some maps include spots denoting critical cable landing points. If these entities are damaged, then the internet connectivity will deteriorate and some websites may become inaccessible altogether. Overall, adverse consequences would be substantial.

Moreover, the coordinates of these places are freely available, as is the case with all internet exchange points between America and Western Europe. One of them is deployed at Mastic Beach, in the urban area of New York’s Long Island. One more cable landing point is located at a beach in Manahawkin, New Jersey.

Other critical internet nodes are in:

- Great Britain

- Tokyo

- Singapore

- Hong Kong

- Mumbai

- Chennai

- South Florida

- Marseilles

- Sicily

- Egypt (its Middle East area plus the Red Sea)

If all these main nodes simultaneously stopped functioning, then the internet isn’t likely to operate like it should. Rather than be the internet in the regular sense, it will turn into a multitude of intranets because the global connection between different segments will be missing.

With that said, the network’s capability of self-recovery shouldn’t be underestimated. Therefore, if the nodes malfunction in an alternate manner, then the initially damaged ones will have been up and running by the time the others are knocked offline.

In other words, the issue will become grave only as long as all nodes become inaccessible concurrently. A scenario like that is quite plausible, and it doesn’t necessarily boil down to the human factor. For instance, the sun – the star we all heavily depend on – can compromise the internet as well.

Solar storms

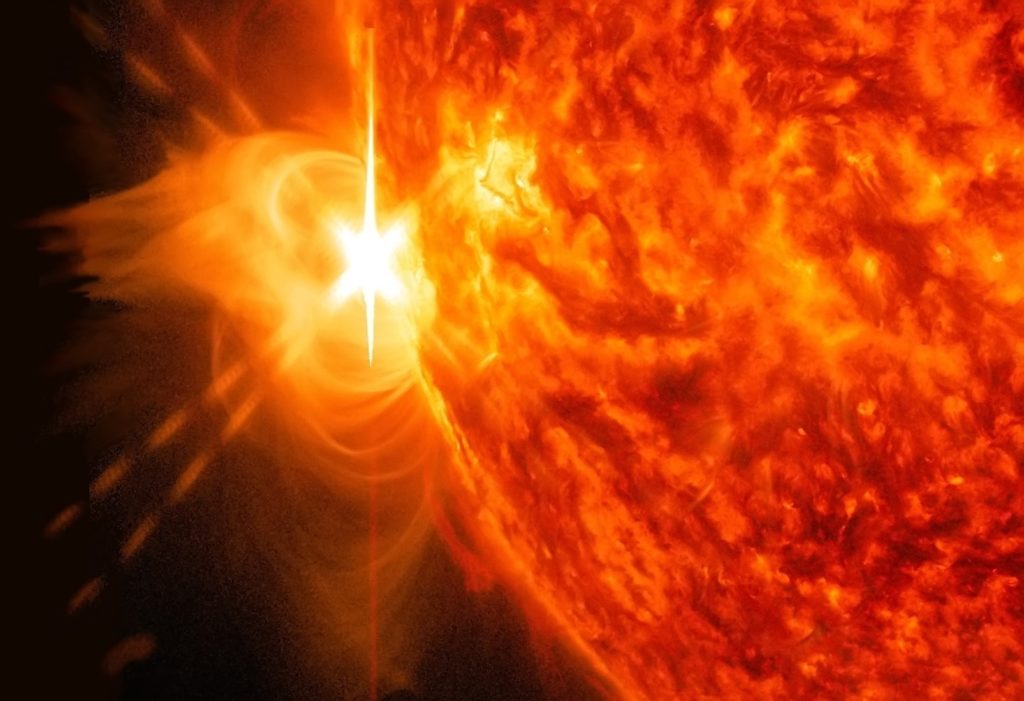

Solar storms sometimes occurs after solar flare events. In this case, the direction of coronal mass ejection from the sun’s surface repeats the route of the preceding flare.

Solar activity follows a cyclic pattern. The full cycle, also known as the Hale cycle, lasts for 22 years and denotes the time it takes the sun’s magnetic field to return to its initial state.

When a solar flare takes place and a powerful coronal mass ejection occurs, the magnetic field around the star cannot retract all of the substance. Consequently, part of the mass travels away at an enormous speed, joins the solar wind and increases the concentration of particles in it, including ones that have greater energy and mass.

The sun loses more than a million tonnes of matter every second, and it loses tens of billions of tonnes during coronal mass ejections. When the Earth finds itself in the way of these ionized substance streams, its magnetic field withstands a hefty impact. This is what causes magnetic storms on our planet.

The essence of a geomagnetic storm revolves around the interaction of solar wind particles with the Earth’s radiation belts, where the former accumulate and generate currents which, in their turn, create magnetic fields in the places of particle concentration. All of this leads to disturbances in the planet’s magnetosphere.

These disturbances can be several days long, with a highly intense stream being potentially capable of impairing the magnetic shield of the Earth so badly that induction currents will occur in all conductive metals. This phenomenon will primarily affect communications satellites, but it may well influence electronic equipment on Earth too.

The menace is so real that Lloyd’s of London, a well-known insurance company, publishes appropriate risk assessment reports for North America.

The solar storm of 1859, also referred to as the Carrington Event, was so powerful that it would have wreaked havoc with the Earth’s entire power grid – if one had existed back then. It caused currents to occur in telegraph wires, which completely disrupted the telegraph connection both in Europe and in the United States.

This solar flare produced 20 times more energy than the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs. Polar lights were seen across the globe, even in the Caribbean. According to statistical records, incidents like that take place once in about 500 years.

Researchers have recently discovered evidence of another flare that occurred in AD 774. It was 20 times heftier. If such an event took place nowadays, not only could it destroy the electrical grid and data on storage devices that conduct electricity, but it could also ruin 20% of the planet’s ozone layer. Analysts claim such a flare may occur once in 1,250 years.

The takeaway for the average user is to maintain data backups. Both tape libraries and other magnetic media, as well as storage devices containing conductive elements or otherwise relying on conductivity for proper functioning – all of these will most likely become unusable unless properly protected in advance. Meanwhile, the use of optical disks still appears to be the most dependable way to store information.

Data centres, network operators and communications

The internet doesn’t equal the network connection only – it’s also composed of the network’s ‘participants’. The bulk of all data is stored in data centres rather than personal devices. The number of these data centers isn’t as large as you might think. In fact, there are a total of 4,424 across 122 countries.

Some are critical nodes of the global network as they host internet exchange points and communications management systems for both physical and virtual private networks. The 13 root DNS servers, which are labelled with the letters A to M and based in 13 data centres, have roughly 200 mirrors.

It means they are deployed in 200 different entities, something the hackers forgot about when threatening to shut down the network. However, the number of communications management nodes is much smaller. In fact, some internet exchange points and backbone control centres are located within one or a few objects.

You may have heard about AMS-IX, an internet exchange point based in Amsterdam. Hosted in the EvoSwitch data center, it’s one of Europe’s major internet hubs.

Meanwhile, Amsterdam is below sea level. Even though EvoSwitch is more than a metre above land surface, flooding is still possible. If it occurs, Europe will be confronted with huge internet connectivity issues.

A probability of transmission equipment being damaged due to a global virus outbreak is sizeable, too. Such a scenario may entail even more serious network problems and a complete denial of access.

The internet will struggle to function without cables and data centres. The surviving intranets scattered across the world won’t be able to exchange data with one another.

However, unless we die of shock over all the cute cats having vanished from YouTube and Instagram, we could reinstate everything over time. Then, once again, we will upload petabytes of adult materials and Google will gladly index it all.

The internet cannot be completely destroyed, it seems, but it is vulnerable to profound disruption and fragmentation into countless intranets.